Once the veil of opacity is removed for how systems function, residents are able to very effectively navigate and intervene to get a more equitable distribution of resources and to change the way systems function into ones that are a lot fairer, more stable, wiser, and have better outcomes.

The origin of climate safe neighborhoods

Throughout our twenty-year history, the Groundwork USA network has worked to undo the legacy of environmental injustice by bringing residents together to transform neglected and underutilized land into community assets. In recent years, the impact of the climate crisis has escalated rapidly – the summers are getting hotter, flooding is happening more frequently, and respiratory illnesses are worsening as heat exacerbates poor air quality issues. These challenges are not shared equally across neighborhoods and our communities, already navigating intersectional environmental, social, and economic justice issues, are experiencing intensifying conditions first and worst.

In 2017, we realized that if we were to truly fulfill our vision of healthy, green, and thriving communities, we needed to better understand the current and projected impacts of the climate crisis, and their origins, to build safer and more resilient communities for the future, in addition to greening neighborhoods now.

True to our core values, we didn’t seek to develop a one-size fits all approach but instead put residents in the driver’s seat to determine what climate resilience looks like in their own communities and equip them with the support and resources to turn that vision into reality. With this goal in mind, we launched the Climate Safe Neighborhoods (CSN) partnership in 2018 and have worked over the past five years with the broader Groundwork community to co-create a model for building the resident capacity in environmental justice communities to prioritize climate adaptation needs and self-advocate for a more equitable distribution of adaptation infrastructure.

The CSN partnership is based on the belief that because our communities don’t look the way they do by accident, they aren’t going to change by accident. To enact change, we first need to understand the policies and systems that have shaped our communities and then work to strengthen the capacity of residents to intervene in these often opaque, complex systems to transform the decision-making process into one based on shared leadership and make the distribution of climate adaptation resources more equitable.

To better understand the root causes of why our communities look the way they do, the Climate Safe Neighborhoods partnership capitalizes on publicly available data and historical redlining maps. We digitally overlay redlining maps over geospatial data ranging from tree canopy and impervious pavement to extreme heat and stormwater risks, visually connecting the dots between the past and the present. Using these tools as platforms for conversations about change and equity, we can move the conversation forward from debating the problem to identifying solutions. Check out the CSN story maps here.

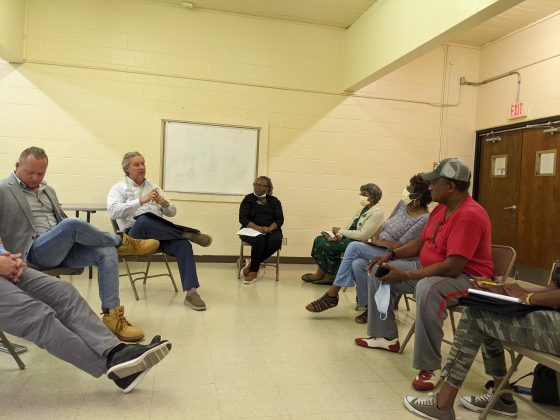

To broaden the number of community members engaged in climate advocacy and build the capacity of residents to self-define the future of their community, the CSN partnership relies on a tiered leadership, train-the-trainer approach. Through biweekly, one-on-one coaching meetings with each Trust’s CSN manager, Groundwork USA builds a foundation with Trust staff around the fundamentals of community organizing, effective community engagement strategies, and the use of geospatial data to facilitate conversations about the past, present, and future! Then, Groundwork Trusts use what they have learned to organize cross-sector partnerships, catalog resident priorities for their built environment, and strengthen the capacity of their own residents to organize for desired changes. Using these skills, Trusts bring together community members and residents through grassroots outreach, create paid CSN Resident Task Forces, meet with local decision-makers, attend City Council meetings, and nurture cross-sector partnerships to intervene in and modify systems that have perpetuated the patterns of climate inequity we see today.

Groundwork Rhode Island, for example, changed the way that new trees were distributed across the city from a first-come-first-serve model to an equity-based approach through CSN partnerships. Read more about Groundwork Rhode Island’s efforts here.

Built into the CSN partnership was the flexibility to be responsive to feedback from the Trusts and local residents, imperative for the success of a program that needs to work for communities with very different cultural, historical, and political contexts. Regular meetings allowed for open communication channels with Trust staff about what was working and what needed adjusting. “If [CSN] had been really prescriptive from the start,” Cate Mingoya, Groundwork USA’s National Director of Climate Resilience and Land Use, explains, “I don’t think it would’ve been successful.”

lessons learned

Over the past five years, CSN has grown tremendously, receiving both national and local recognition. From the first cohort of five Trusts, the partnership is now active in 16 cities, soon to be 18 as we get our Climate Safe Massachusetts regional partnership off the ground this year. This regional partnership will embody the same overarching methods of CSN but will also focus on connecting residents from all four communities to share knowledge, build collective power, and take advantage of federal, state, and local investments in environmental justice. The scope of the partnership has also grown, with most Trusts participating in CSN adopting its organizing framework as the connecting tie for all of their programming, unifying their land restoration work, youth programs, and others under one umbrella.

Through the many iterations of the program, we’ve been able to narrow in on core elements that make this partnership so successful across regional, political, and environmental differences.

It’s neutral. The CSN approach allows communities to have conversations about inequity and systems change in a non-confrontational way that everyone can understand. In our Trust communities, as we see in the United States as a whole, it is challenging to talk about issues of race and discrimination. Using maps to visualize climate vulnerabilities “removes some of the strain of you vs. me, us vs. them, my ancestors vs. your ancestors, without erasing a real and painful history,” Cate points out. “The structure of CSN allows us to take a pause and say, ‘we know there are a lot of confounding factors that go into this, but let’s look at the history, let’s look at where we are now, and let’s talk about what we’re going to do about it together.’ And that’s made a believer out of many people who felt like systemic racism doesn’t exist or that climate change isn’t human-caused.”

It’s concrete and visual. People respond to this methodology. When residents are empowered to speak about the connection between historical policies and practices and current experiences, with the data to back it up, their decision-makers are forced to consider uncomfortable questions and decide to what degree they want to participate in change. The structure of CSN allows communities and local governments to talk about their climate challenges and visualize the differences between neighborhoods, ultimately leading to more concrete, specific asks.

It’s community-focused. Through CSN, residents are treated as experts and compensated for sharing their experiences and knowledge in creating culturally and socially appropriate climate adaptation solutions. This is critical everywhere, but especially in environmental justice communities that have experienced deep trauma at the hands of outsiders who come in to solve problems.

There’s a misconception that communities of color and low-income communities don’t prioritize environmental justice issues. Our work has proven that this couldn’t be farther from the truth. “What’s different about our approach,” Cate says, “is that we start from the understanding that the people we’re working with are whole individuals. We’re not coming in to change the core of their being. Everyone we’re working with is smart and capable; they have visions and goals and priorities. We help facilitate the realization of [those goals] by bringing in different resources and taking on some of the organizational burdens that other people just don’t have time for. We start by viewing the communities not as spaces that exist in deficit but instead come from an abundance mindset. There are amazing, wonderful, valuable people who live in this space and they have amazing, wonderful, valuable ideas.”

It’s based on mutual trust and relationship building. An important component of CSN is the foundational relationships at the local level between Trusts, community members, and other stakeholders. As Cate explains,

“That long history of people-centered work is what built the foundation to make CSN possible. In absence of it, no amount of maps, funding from a foundation, or [community] coordination, would have been able to close that gap of trust. [Environmental justice] communities have been taken advantage of and ignored for so long by people who have money and traditional power that outsiders coming in and doing that kind of work just wouldn’t have happened. But because we had that long history and relationships through the community, they were open to us and this new idea.”

CSN is proof that environmental justice work and building power at the community level are inextricably linked. For this work to be successful, it must be rooted in community needs and community-driven organizing.

We are excited to see how the CSN partnership evolves in the next five years.

Interested in learning about how to implement the CSN framework in your own community? Check out our Taking Action Guide!