The science world has a diversity problem—and the conservation and environmental sciences are among the worst offenders. A 2014 analysis of employment patterns in the sciences found people of color disproportionately underrepresented in “green” STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) occupations. Quoted in a recent Grist article, Pomona College Associate Professor Adam Pearson, one of the researchers who conducted that analysis, noted that “In green STEM fields—broadly defined as conservation sciences, environmental sciences, climate-related sciences, earth, and atmosphere—you find up to twice the level of disparities, sometimes up to three times the level of disparities as you do in other physical sciences.”

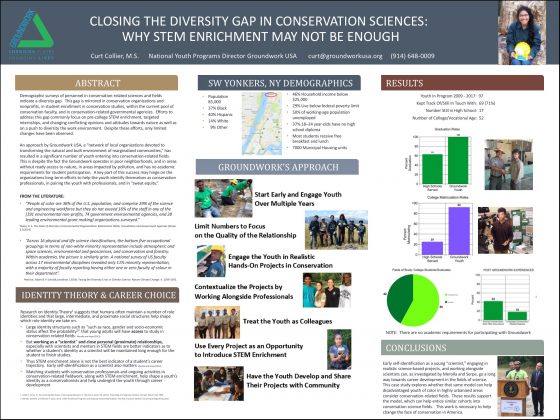

These disparities are mirrored in conservation organizations and nonprofits, as well as in student enrollment in conservation studies, among conservation faculty, and in conservation-related government agencies. In her groundbreaking 2014 report, University of Michigan Professor Dr. Dorceta Taylor found that “People of color are 36% of the U.S. population, and comprise 29% of the science and engineering workforce but they do not exceed 16% of the staff in any of the [191 environmental non-profits, 74 government environmental agencies, and 28 leading environmental grant making] organizations surveyed.”

These disparities are mirrored in conservation organizations and nonprofits, as well as in student enrollment in conservation studies, among conservation faculty, and in conservation-related government agencies. In her groundbreaking 2014 report, University of Michigan Professor Dr. Dorceta Taylor found that “People of color are 36% of the U.S. population, and comprise 29% of the science and engineering workforce but they do not exceed 16% of the staff in any of the [191 environmental non-profits, 74 government environmental agencies, and 28 leading environmental grant making] organizations surveyed.”

Typically, efforts to increase the representation of people of color in green STEM fields focus on pre-college STEM enrichment, targeted internships, changing conflicting opinions and attitudes towards nature, and on an overall push to diversify the work environment. These are all important undertakings in their own right. Yet despite these efforts to diversify green STEM fields, only limited gains have been observed.

When you look at Groundwork youth, however, a different picture emerges.

Young people of color make up over 90% of Groundwork Green Teams. Groundwork Trusts operate in low-income neighborhoods with underfunded school systems, in areas impacted by pollution and without ready access to nature. There are no academic requirements for youth participation in Groundwork programs. Yet the preponderance of data suggests that youth enrolled in Groundwork Green Teams have higher high school graduation and college matriculation rates than the high schools their Trusts serve.

A significant number of Groundwork youth also pursue conservation- and science-related degrees and enter into conservation-related fields after their involvement with a Groundwork program. At Groundwork Hudson Valley alone, of the college-age youth Groundwork remained in contact with after their Green Team participation from 2009 to 2017, 43 percent went on to pursue conservation work after Groundwork and 18 percent completed conservation-related degrees.

Cultivating Science and Conservation Professionals

Groundwork Trusts have a solid track record of engaging youth in green STEM fields and conservation science. So what are we doing right?

Groundwork Trusts’ conservation and community revitalization projects, from redeveloping polluted brownfields to restoring the habitat of urban rivers to repairing trails and renovating historic buildings in national parks, provide excellent opportunities to engage youth, hands-on, in environmental and conservation science.

STEM applications take many forms at Groundwork Trusts. How many yards of soil do you need to fill three 4×8 garden beds? How can statistics help you predict the number of invasive plants you’re likely to find in a wildlife refuge? What nutrients does a tree need to thrive in an urban environment? These are the kinds of questions Groundwork youth ask—and need to answer—over the course of typical Green Team activities.

Trained as a scientist, Curt Collier, Groundwork USA’s Director of National Youth Programs, encourages Trusts to use every Groundwork program and activity as an opportunity to introduce youth to elements of STEM enrichment and training. Last month, he presented a poster on Groundwork USA’s approach to closing the diversity gap in conservation sciences at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), a venerable professional organization that promotes scientific and technological excellence across disciplines and one of the oldest scientific societies in the country.

“When I got to the meeting, I realized they’re all struggling with the same topic—how to engage young people, and especially youth of color, as scientists—yet we seem to be offering some solutions. When I presented my research, a lot of people were excited that Groundwork is so successful.”

What elements contribute to that success? Groundwork Trusts start young, recruiting high-school age youth to participate in Green Teams, and often engaging them over multiple years. Moreover, Green Teams are deliberately small, as limiting the numbers allows Groundwork staff to build quality relationships with Green Team youth.

An emphasis on professionalism is also critical. When Groundwork youth visit public lands, they’re not tourists.They perform real sweat equity work, developing deep connections and a lasting sense of stewardship over the parks and refuges they help improve.

That professionalism also extends to pairing youth with conservation professionals in the field and finding ways to help youth personally identify themselves as scientists. As Curt explains, “Research shows that the best way to engage young people in science is to hook them in on meaningful projects that are science-related, and treat them as professionals. That’s what we do in our Green Teams and youth corps programs. We aim to treat our youth as colleagues, not just students. Self-identity is important in the development of young scientists. So the more our Trusts can help young people come to see themselves as conservation or environmental scientists and professionals, the better.”

The result is a win-win: for the youth, who prepare themselves for careers in conservation or conservation-related sciences, and for their communities, which benefit from the youth’s increasing expertise and knowledge.

Deeply invested in these outcomes, Curt understands just how much is at stake: “For me, Groundwork is about engaging the next generation in conservation, it’s preparing the next generation to take on the work that many in communities are trying to do. These problems don’t have easy solutions, so getting youth interested in the science behind them—and conservation science especially—is one part of what we need to do to prepare them.”