The road ahead for people and planet looks alarming at best, according to two major new climate reports, the United States’ Fourth National Climate Assessment and the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5ºC from the United Nation’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Both paint a picture of a rapidly draining hourglass. When the last grain of sand falls — potentially as early as 2050 — we are set to suffer tremendous social, financial, cultural, and human losses unless the world’s largest nations make bold and difficult strides towards decreased climate-altering emissions.

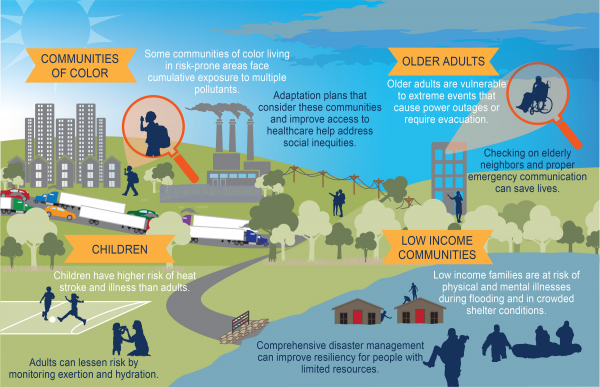

While some governments debate sweeping policies to reduce climate emissions and others settle for inaction, many communities across the world are already contending with the consequences of wetter, hotter weather. But climate change will not impact all neighborhoods equally. Low-lying and heavily paved areas are more vulnerable to extreme heat and flooding — and it’s no coincidence that people of color and low-income families live in some of the neighborhoods most at risk.

In response, Groundwork USA and five community-based Groundwork affiliates are moving to the front lines of the fight for climate justice by embarking on a major multi-year Climate Safe Neighborhoods project to reduce heat- and flooding-related risks in neighborhoods with histories of race-based housing discrimination.

Using federally commissioned “redlining” maps and urban heat and flood risk data, Groundwork Denver, Groundwork Elizabeth (NJ), Groundwork Rhode Island, Groundwork Richmond (CA), and Groundwork RVA (Richmond, VA) will mobilize local stakeholders to influence climate resilience policies, programming, and investments that reduce the impact of heat and flooding in high-need neighborhoods. This project is supported, in part, by a grant from the Kresge Foundation.

What does climate justice have to do with housing discrimination?

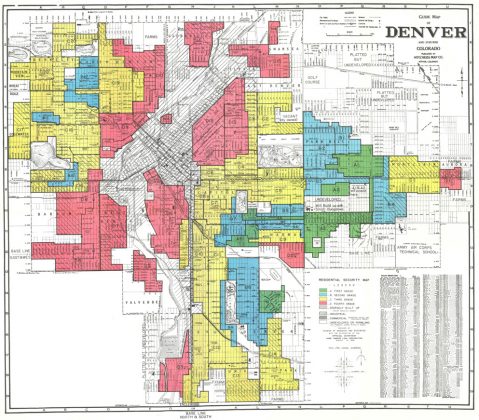

In 1935, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board authorized the creation of “residential security maps” to indicate the desirability of real estate holdings in 239 cities across the United States. These maps were used alongside the Federal Housing Administration’s underwriting manual to decide who got home loans and who didn’t. Wealthy, white neighborhoods on the edges of cities were outlined in green and marked as safe bets for mortgage lending. Those dense neighborhoods outlined in red (or “redlined”) — often communities with majority black or brown residents — were considered too risky for loans.

Throughout our nation’s history, people of color, immigrants, and low-income families were directed to and often forcibly relocated to low-lying areas both prone to flooding and zoned for industrial use. A lack of green spaces and municipal investment have left these areas hotter and wetter than surrounding neighborhoods.

In addition to codifying discriminatory practices that furthered racial and income-based segregation, these redlining maps forced people of color to stay in declining neighborhoods and prevented them from owning their own homes, the primary vehicle for wealth building in the United States to this day. While redlining was officially outlawed under the Fair Housing Act in 1968, banks across the country have been charged with redlining by the Department of Housing and Urban Development as recently as 2017. The legacy of government-enforced racism and depressed homeownership rates amongst people of color lives on.

As climate change increases the number of days above 90 degrees and exposes low-lying communities to more frequent and severe flooding, cities and towns across the country have a huge climate justice issue on their hands. Low-income residents and people of color didn’t end up in these areas by choice, but they must now contend with threats to their health, safety, and economic prosperity brought about by a changing climate. Extreme heat will make chronic illnesses more difficult to manage and will hasten the deaths of many due to kidney failure, cardiovascular stress and respiratory complications. In addition to the health consequences likely to most impact those least able to afford quality medical care, the financial cost of climate change is predicted to be tremendous. Damages from climate change in the United States are expected to total trillions of dollars in destroyed property, lost productivity and wages, increased medical costs, and premature morbidity; this has the potential to shrink the U.S. economy by a staggering 10 percent.

Groundwork’s Role

If we’re to avoid climate-exacerbated harms such as increased asthma rates and death from heatstroke and flooding, widespread property damage, and reduced economic productivity, changes to the physical environment are urgently needed. Groundwork USA and the five participating Groundwork Trusts are taking a grassroots approach to organizing residents and non-resident stakeholders to weave those changes into housing production plans, master planning processes, government programming, and more.

In year one, the Climate Safe Neighborhoods project is dedicated to collecting, mapping, and interpreting local climate vulnerability data with the assistance of NASA and Groundwork Milwaukee’s GIS Program Manager. Additionally, participating Groundwork Trusts will research local-level health impacts of extreme heat and flooding and mitigation measures, and will determine strategies for engaging stakeholders, getting the word out about the dangers of extreme heat and flooding, and influencing local policy and practice.

After researching, developing, and prioritizing community-backed climate mitigation measures, the Groundwork Trusts will organize and advocate to effect change at the local level. Working with stakeholders, they will use data on the historic origins and health impacts of, and solutions to extreme heat and flooding to advance the integration of environmental justice-focused climate mitigation measures into policies, programs, and investments. Groundwork urban conservation corps programs will also incorporate climate resilience measures into their work. Groundwork USA will use the data collected by the Trusts to advance equitable resilience strategies nationally.

It will take a broad coalition of stakeholders — from residents to teachers to small business owners to city councils — to prioritize the protection of our communities in the face of a changing climate. This work will not be easy — but longstanding community roots of the five Groundwork Trusts and our role as trusted conveners will be key to moving the needle on climate justice.

–Cate Mingoya (cate@groundworkusa.org) is Director of Capacity Building for Groundwork USA